Showcase of student projects

Robert’s passion for woodwork and the sharing of this knowledge is hard to put into words.

But there is probably no greater evidence of this than in the variety of the work produced by his students or the stories behind them. To know the students and their work is to know Robert’s method of teaching, and there is no better way to showcase this by putting them together. The purpose here is not to highlight individual talent or skills (of which there is an abundance of), but the way in which Robert works with students is as unique as his approach to woodwork.

The joy and playfulness of woodwork

The joy of woodwork comes from many different sources. For this student, the fun and playfulness of creating a Jatz cracker as a gift involves some very serious techniques and patience that is gained from completing the project.

Robert’s comments:

All woodcarvers discover that some aspects of their personality assist them as they work, while others cause them problems. Only the mix changes. As you can see, the student did an excellent job.

I constantly say to my students that they need to ‘creep up on the final form’, as they work around and around or over and over their carving. The rough form emerges first, then slowly develops clarity as lines and details are added. Any attempt to short circuit and hurry this process, especially for a beginner, is likely to end in frustrating failure. Once wood is removed, it can’t be put back.

This student has always understood this, and has always been content to take as long as necessary with her carvings. The results have always been excellent.

The progression of technique and skills

Progression is an important aspect of the learning process, as demonstrated by the successive increase in the number of the ribbons carved into each new piece of artwork.

Robert’s comments:

Hape Kiddle, the Master of the Mobius, is well known to my students, and quite a few have attempted to copy some of his forms. They are deceptively simple looking, but in fact are anything but. To put it another way, they are guaranteed to do your head in.

Carving the mobius itself is not the problem. It is making it beautiful from every angle – the central challenge of sculpture – that is so difficult.

To be successful, you have to learn the form through repetition, learning little by little from your failures, and never being afraid of failure.

This student has learned the mobius form this way, and now consistently produces excellent results.

A strangest quirk of this student, for me, is that he loves sanding, but I have to say, the results justify the time spent.

Breathing new life into old materials

The first piece on the left came from two separate discoveries in bins distant apart, while the second piece comes from a two pieces of a discarded table. The principle of turning what might otherwise be seen as a flaw in the wood into a feature is highlighted in the second piece.

Robert’s comments:

These two photos typify two different types of forms. The first shows an organic form of flowing lines; the second is a geometric, fixed form.

The first type is much more difficult than the second as it is constantly evolving as it is carved, and must be constantly judged from different angles. Changing something in one viewpoint usually also changes one or more other viewpoints, so it becomes a juggling act.

The second form is fixed from the beginning, so care has to be taken to get it right in the planning or design stage. It does show, however, the visual power of repetitive forms.

Both were carved by the same student, from salvaged wood, working with whatever possibilities the wood allowed. An odd shape, or a flaw such as a knot in the wood, can be decisive in suggesting a particular design that takes advantage of the flaw, either by making it part of the carving, or by carving it away and working with the good wood that remains.

Geometric aesthetics

Beauty comes in all shapes and forms, whether it is the clean straight edges in a geometric shape, or the smooth and repeating patterns mimicking nature. A simple rule of thumb or guiding principle to woodwork aesthetics is that the shape or form should be pleasant and easy on the eye from all viewable positions/angles.

Robert’s comments:

Only a certain type of mind will respond to the geometric challenges represented by those photos.

The first two photos are of interlocked geometric forms which, if I remember correctly, the student first carved them as solid forms – for example, two similar sized cubes interlocked at some angle to each other.

The next step was to reduce the cubes to narrow ‘sticks’ representing the edges of the cubes, in the process carving away the sides of the cubes and hollowing out their insides. This can be done with all sorts of geometric forms, depending on how far you want to push it. Needless to say, these can also do your head in.

The final form is the well known nautilus half-shell, one of the most beautiful natural forms. Carving this not only required the hollowing out of all the compartments, but also meant carving the bottom of each compartment to conform to the curve of the underneath of the shell form.

The human story behind the artwork

Behind the deceptively simple patterns and smooth lines of the Krenov style chessboard and storage unit lies the technical precision of the craftsmanship required to bring the vision to life.

The box and table was on show at the Maleny Wood Expo alongside other examples of fine woodworking.

The enduring quality of the woodwork ensures that one day it will make for an excellent piece of heirloom.

Robert’s comments:

Although I no longer teach furniture making, I do continue to welcome this long term students to my class each week to work on these types of projects. Long term students highlights the fact that my classes are not only about learning new skills – they are also about friendships, and enjoying the company of your fellow students.

Carving, or any craft, requires the use of both your mind and your hands. It provides a never ending challenge and can absorb as much time as you want to devote to it. If you are lucky, you will discover you are passionate about it. You might also find that you are very good at it.

After all this time, this student does not require a lot of my time, beyond the occasional discussion about a design, or a particular technical problem. Although he has a good home workshop, some of my machines he enjoys being able to use.

He has proved to be a meticulous furniture maker, much more patient than I am, and consistently produces excellent work, as the photo shows.

Good enough is definitely not good enough for this student, who will persist until everything is is spot on – a very rare attribute in my experience.

Often the first step towards mastery of the craft is to learn and mimic the masters. Here the student demonstrates technical execution with some personal touches to recreate Ernst Barlach’s sculpture in a slightly more minimalist style.

Robert’s comments: coming soon

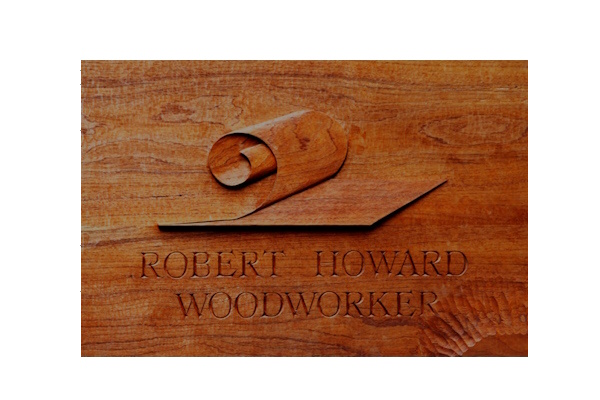

Lettering in woodwork combines the concepts used in calligraphy to the techniques of woodworking in a harmonious manner, as evident in this delightful creation of a signage for a section of a family home. The student creates a beautiful piece with a personal story etched in the artwork.

Robert’s comments: coming soon

In the past, the utility and craftsmanship of woodwork integrated seamless together. Here we have an example of a student creating a stunning piece of artwork with a practical purpose in the past. This sundial makes for a fine centerpiece of a garden, demonstrating the precision of lettering skills and the creativity of woodcarving techniques.

Robert’s comments: coming soon

Often the work of the teacher is something that students can only hope to aspire to but never reach, but here we have an example of a piece of work inspired by Robert taking out the Wootha Prize for Sculpture in 2024. “Flow” elegantly captures the fluidity of a wooden ribbon winding into a bowl, only to be effortlessly released and drawn back into the form, embodying a seamless flow of movement and harmony.

Robert’s comments: coming soon

The instructor pictured here posing with a student’s work – an intricately carved picture frame for a print work. Always encouraging and generous in advice as well as praise.